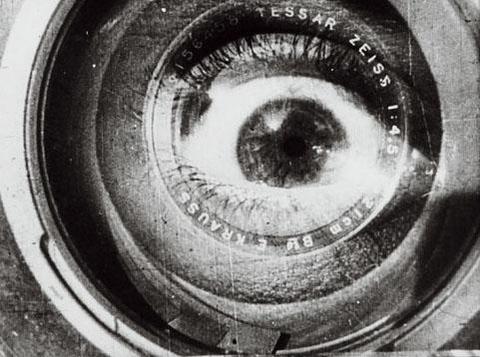

To think, Dziga Vertov's The Man With a Movie Camera came out more than 74 years ago. Things have changed in cinema since then, yet the influence Vertov's film has had on movies is immeasurably towering. Film was already entering the sound era and silent pictures were slowly dying, yet "talkies" weren't fully fleshed out and the quality of the product was lacking. There was something missing. It took Vertov's experimental film to pave the way for the next 80 years of cinema to come.

There aren't many films as influential as Vertov's masterpiece of sound and image. One can think of Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless in 1960 and its invention of the jump cuts but even that film can't compare to Vertov. "It stands as a stinging indictment of almost every film made between its release in 1929 and the appearance of Godard’s 'Breathless' 30 years later," film critic Neil Young wrote, "and Vertov’s dazzling picture seems, today, arguably the fresher of the two." Godard is said to have introduced the "jump cut," but Vertov's film is entirely jump cuts.

Before Man With A Movie Camera most films had shots that lasted for many seconds, if not minutes. The average shot length in 1929 was of 11.2 seconds. In the blink of an eye Vertov decided to make an experiment and have his shots last a much shorter duration. The average shot length of his film ended up being a mere 2.3 seconds, a feat completely unheard of back in 1929. To give you an example Michael Bay's Armageddon released in 1998 also has an ASL of 2.3 seconds.

Vertov saw how cinema was stuck in a tradition of being shot like a stage play. I can think of Josef Von Sternberg and his Marlene Dietrich pictures which, to my eyes at least, haven't aged very well because of the staginess and theatricality that infused their every frame. The same could be said with many of that films at that time that refused to break the wall of theatricality.

It wasn't just the ASL that was mind blowing, Vertov decided to make an experiment and to push the boundaries of what cinema can do. He combined his images of daily life in communist-era USSR with a soundtrack that melded perfectly with his images. It's as if the music was made to gel with the celluloid he shot. There isn't anything dramatically gripping in the film as much as there is a bombardment of contagious cinematic joy. The sheer rush of experimentation. In fact this experimentation still seems fresh by today's standards. 80 years later, Vertov's masterpiece still has a striking effect with a whole new audience.