I recently finished watching all eight episodes of Steve Zaillian’s “Ripley,” currently available to stream on Netflix. The only question I have right now is if this isn’t the best shot TV series ever made, then what is? The visual language is second to none.

If you believe there’s been a more beautifully shot show then please, by all means, name it. The other contenders I’d include: “Mad Men”, “Breaking Bad,” “Chernobyl,” “Mindhunter,” “Better Call Saul,” “True Detective” (S1), and “Fargo.”

Andrew Scott stars in “Ripley,” which is based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel. The “All of Us Strangers” actor, so good here, portrays the sinister grifter, Tom Ripley, originally portrayed by the likes of Matt Damon, John Malkovich, Alain Delon and Dennis Hopper. Scott’s take is another essential entry to the character.

If you’ve seen Anthony Minghella’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” then the plot is fairly similar here. Ripley is hired by a wealthy man to travel to Italy to try to convince his son, Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn), to return home. If you’re familiar with the source material, then you know what happens next. Set in 1960s Italy, it’s a “love” triangle between Ripley, Dickie, and Dickie’s fiancée, Marge Sherwood (Dakota Fanning), with an added dose of murder.

Zaillian wrote and directed all eight episodes. He is one of the best Hollywood screenwriters of the last 30 years. His credits include “Schindler’s List,” “Moneyball” and “American Gangster.” He’s also directed three films: “Searching for Bobby Fischer” and, less successfully, a botched remake of “All the King’s Men.” However, I did not expect anything close to this from him.

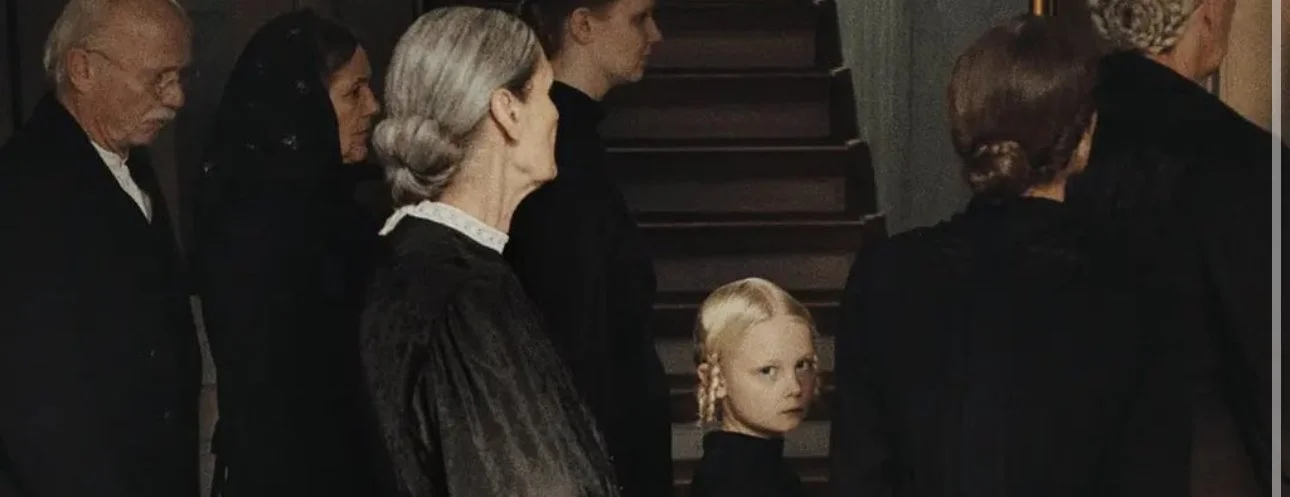

“Ripley” was shot in a chilly, textured black-and-white palette — which turns out to be a very inspiring creative decision. Best of all, former PTA regular, Robert Elswit (“There Will Be Blood,” “Punch Drunk-Love”) is credited as the cinematographer on all eight episodes. He shot the series with Arri Alexa LF digital cameras. The number of reflections, shadows and patterns is breathtaking to behold. The usage of negative space is exemplary.

I also love how, throughout “Ripley,” Tom’s fascination with Caravaggio ends up making the series parallel the artist’s baroque 16th century paintings. The Italian painter was famous for his use of contrasting light and dark, and it looks like Zaillian/Elswit tried to shoot the series that way, constantly manipulating light and shadow.

There’s also a TON of static shots in “Ripley,” with either little to no action, or movement in and out of the frame. This gives the viewer time to appreciate the composition and arrangement. Take, for example, the pivotal 20-minute boat scene between Tom and Dickie, an exemplary display of horrific tension delivered via static extreme closeups of the crime and a series of stunning wide shots of the boat.

The oppressive atmosphere, the gorgeous framing of the shots, it’s all just utterly intoxicating. This is a fearless series framed in a meticulously slow and scholarly way. Almost every single damn shot looks like a museum painting. Some are just jaw-dropping. “Ripley” makes the case that cinema can be found on the small screen via a series. It’s one of the very rare examples of that; the others I can think of, off the top of my head, would be Lynch’s “Twin Peaks: The Return” and Kieslowski’s “Dekalog.”

However, it’s probably not the best Ripley adaptation we’ve gotten, especially with Wim Wenders’ “The American Friend,” Anthony Minghella’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” Liliana Cavani’s ultra-underrated “Ripley’s Game” and René Clément’s “Purple Noon” knocking at the door, but Zaillian’s series is an immensely impressive atmospheric twist on familiar material.