It’s been a long time since making traditional or even vaguely conventional “movies” has interested legendary French New-Wave filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. If anything, the director’s movies over the last 20 or so years have been experiential audio/visual collages more interested in pictures, sounds, cuts, and de-saturation; a maddening barrage of dadaist statements. Even with all that being said, his latest, “The Image Book,” playing in competition at Cannes, should be considered as radical a Godard-ian statement as any.

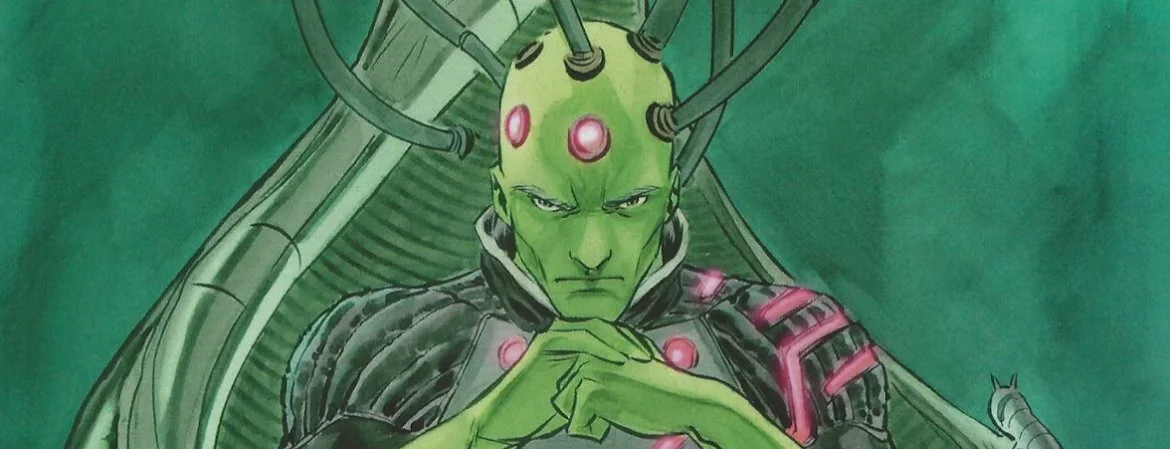

Using images from the beginning of cinema to today, the legendary filmmaker cuts, splices and, let’s be honest, just throws visuals into this burning skillet of angry MONTAGE. And the word definitely deserves the ALL-CAPS treatment because that’s exactly what this latest film is. The picture is a dive into the sensory, aesthetic and, this being Godard, the radically political.

One yearns to be transported by his sonic and tactile experiments–after all, his last film, “Goodbye to Language,” was an unequivocally gorgeous amalgam, in 3D no less, and represented his best work in years. “The Image Book,” sadly, is sometimes too impenetrable.

More of a visual experiment than any kind of movie, there are passages that evoke the poetic as political. Whatever interests Godard is only hinted at to the audience, with abrupt cuts and purposeful flow interruptions that seem to indicate the filmmaker wants to frustrate rather than invigorate. This is an art exhibit disguised as an 85 minute product that has Godard reveling in the endorphin rush of posing inaccessible questions, not to mention many of the ugly images and sounds perpetrated on-screen.

No, this is not “The Avengers,” but Godard, a cinematic radicalist, seems to be at the pinnacle of his pretension here. Where to start when describing the “plot?” Forget it. Images ranging from Youssef Chahine to Hitchcock unfurl at a rapid, ADD-styled pace. Not to mention the uglified, and non-pixelated, assault of furiously angry stock footage. There’s another Godard-ian “statement” on the Holocaust, but we’re not really sure what he’s trying to say because the clip lasts all of four short seconds. The beautifully-realized 3D experiment of “Goodbye to Language” is replaced by a nastily vicious tone of resentment for the outside world.

A momentary reflection on the Middle East is thoughtful and concise; Godard suggesting Arabs suffer from the richness of their ground. It seems like he has sympathy for revolutionaries “who can only launch bombs,” but are actually helpless in the face of the grander picture. Does the 87-year-old filmmaker also believe himself to be a revolutionary? After all, he was championed as one in the early ’60s, and then followed suit by championing some of the most puzzling political figures of our time. Who knows?

Godard overloads each sequence in “The Image Book” with dozens of different films from Hollywood’s “Golden Age” to the unheard gems of world cinema. This magma of scenes and actors, known and unknown, can be interpreted according to everyone’s own experiences. Because nothing is explained, the images land on the viewer’s retina at such a fragmented and furious pace that it’s often impossible to interpret the experience. It’s only after you leave the theater that you try to assemble its incoherence, like a puzzle with pieces that don’t seem to fit.

Some audiences will naturally loathe “The Image Book,” some will find moments of transcendence within, and others will leave perplexed and baffled. And that’s OK. “The Image Book” demands digestion in a purely personal way.

Past and present, along with reality and fiction, seem to collide in this phonic, sensory world. As meaningless as Godard’s epileptic montage often feels, some moments do form a kind of coherence; the anger and revulsion for the horrors of war being normalized on television. Maybe this is just the message from the great beyond of an unfathomable cinematic mind warning of the incomprehension of the world that surrounds us. Godard surely does not care what we think.