There are movies that gain traction and relevance once political or social events happen. Bonnie Cohen and Jon Shenk’s “An Inconvenient Sequel” gained a lot since Trump’s recent withdrawal from the Paris climate accord agreement. In fact, the Paris accords plays a very big role in “An Inconvenient Sequel,” with the last half hour solely dedicated to the nitty gritty, behind-the-scenes look at how that essential international deal came to be.

“An Inconvenient Sequel” is Al Gore’s state of the union address, an alarming document of accelerating change and diminishing time. In fact, the notion that time heals everything and compels us to realize our mistakes is a key theme in Cohen and Shenk’s film. David Guggenheim’s 2006 milestone “An Inconvenient Truth” helped bring global warming to the forefront of the mainstream conversation. It even affected a shift in the political spectrum. If that original film felt like a lecture with Gore guiding us through a power point presentation, then this sequel is more cinéma vérité, following Gore in a rather passionate and angry mood throughout as he wheels and deals his way to save the planet. In a summer filled with superheroes, Gore turns out to be the most authentic and resonant of the lot.

“An Inconvenient Sequel” is Al Gore’s state of the union address, an alarming document of accelerating change and diminishing time. In fact, the notion that time heals everything and compels us to realize our mistakes is a key theme in Cohen and Shenk’s film. David Guggenheim’s 2006 milestone “An Inconvenient Truth” helped bring global warming to the forefront of the mainstream conversation. It even affected a shift in the political spectrum. If that original film felt like a lecture with Gore guiding us through a power point presentation, then this sequel is more cinéma vérité, following Gore in a rather passionate and angry mood throughout as he wheels and deals his way to save the planet. In a summer filled with superheroes, Gore turns out to be the most authentic and resonant of the lot.

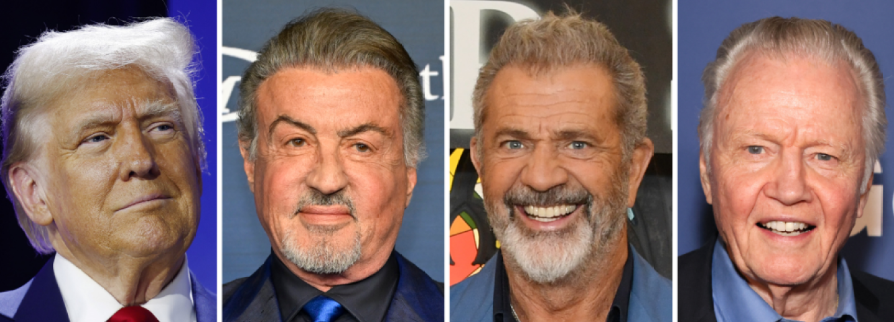

I spoke to Shenk and Cohen about their movie and what its significance is now that we are in the Trump era

It was great seeing this film; how do you envision this in the world of the documentary? There are so many kinds of documentaries and this was clearly a kind of advocacy film.

BC: So the film came to us via Participant media, who made the first film. Advocacy is what they do, so we knew going into this that’s what we were going to be doing. There’s going to be an education to be had and an activism to be had within the film simply because of who the producers were. Jon and I like to make deep, emotional films, the last film we made was called “Audrey and Daisy” and before that “The Island President,” which was about the President of the Maldives. When asked, or given the great honor, of making the sequel to this incredibly important film that came out ten years ago, we thought okay how can we take it, own it and make it into something that’s going to have some emotion and some inherent narrative drama. That was a great challenge, we met Al in July of 2015, he is such a Southern gentleman and had us over at his house in Nashville. He showed us the lengthy version of the slideshow and it was immediately obvious to us, as soon as he started talking about all the places that he collects his information, the constant digging that he does all around the world to keep his slideshow up to date for whichever country he has a presentation in. We thought we could find some inherent drama if we started to follow him to all these various countries, have a snapshot of his everyday life. Al also has a whole other layer, he has in him personal drama, failure, and success, so we wanted to deliver something to the audience that was also more than just facts of the climate crisis.

How much access did he give you guys inside his life?

JS: Tons. I mean, you see it in the film where we made this decision to follow him everywhere. The drama that unfolded in Paris, at the climate accords, was just insane, it was almost like a political thriller in our minds and our lead character was clearly involved in trying to, you know, do everything he could to make the deal a success there. He didn’t say no to us too much. He pretty much was game for anything.

BC: He’s a great lover of cinema by the way. He’s seen everything and he loves documentary. Once he got that we were trying to make a “Don’t Look Back,” something that would show him in his real, authentic self, he got even more interested in helping us with the access.

JS: Of course, people he’d meet wouldn’t always say yes, but he’d tell us “we’re going to India and the ministers might not think the camera is the right thing to do in the meeting,” but he would help us make the case and we had a pretty high batting average with this film. So, to answer your question, we had a lot of access.

You mentioned “Don’t Look Back.” Was that one of your main influences with this film? I went into this movie with the notion that it might be centered around another slide show, but I was pleasantly surprised by how it really separated itself from the first movie with its cinéma vérité style.

BC: Jon is the DP, he shot the whole movie, he’s one of the country’s best “behind the scenes” photographers, so he’s not just capturing the scene for what it is he’s also thinking about the edit, so the combination of the slideshow, which Al was going to do, was very appealing to us, we found like we had kind of a rock star subject, he’s not Bob Dylan, but he’s Al Gore, and often in the past the public did not have access and we didn’t want that to happen again.

JS: D.A. Pennebaker was at our screening. It was such a thrill because this guy literally invented the idea of the “fly on the wall” documentary. I told him “I can’t believe you’re here” and he said “Jon, you’ve managed to do what great documentaries do which is that you’ve brought a person back to life and to come to see a movie like this on a week night is pure magic.” As you can imagine, my heart swelled.

“An Inconvenient Truth” really brought climate change to the forefront of the conversation, it really helped a new generation be aware of it. What were you hoping for with this sequel? It’s a companion piece, but it’s also its own film.

BC: I think the first film was a lightning rod that just went everywhere. It awakened the world community to global warming. I think people were scared, educated but scared, it was our hope with this film that we would jump off from there and that we would kind of take the science and update with what was going on with the climate crisis. As Al predicted in the first film, things have gotten a lot worse, but the huge difference from then to now is that we had, at least, some hopeful news that we could deliver, which was that the sustainability revolution was here and it was just a question of how quickly the world hops on the train and rides it. It’s not like we must throw up our hands anymore, we actually have it in us to do something about it. So, we felt, okay if people don’t feel paralyzed with fear and despair and if we can communicate it through Al’s passion that would hopefully translate to viewers.

What do you think has held the Paris agreement together even after Trump’s decision to leave the accords?

BC: I mean, it’s interesting, Al was really afraid other countries were going to follow suit after the U.S. decided to pull out. The truth is people have doubled down and they’ve not only stayed in but recommitted with further goals that they had had with themselves in Paris. We say it in the documentary, the American people will lead, but the truth is that mayors and governors and populations in this country have committed to keeping the goals of Paris and it’s possible for us to do it on the local and state level. Al now talks about how if you want to physically pullout of Paris there are so many steps along the way for you to do it, years to go by, that in order to complete a pullout of the U.S. with Paris, you would only be able to do it the day the next president takes office.

This was all show from President Trump.

BC: It’s like everything else he does.

JS: Well, he’s playing, as we all know, to what he thinks got him elected, which is these “working class” middle-country people that are suffering, the irony is that he is ultimately punishing these people because other people are looking at his announcement of Paris and saying “Hey, great, you don’t want to be in the solar panel business, we want to be in it.” China and India want to be in it, they will gladly take the jobs. You know, solar and wind are already employing far more people than the coal industry and it’s growing every day.

Gore says in the documentary that he was ready to serve in any way necessary during the Paris agreement. He’s been the voice for climate change and what we need to do for many years. It seems like he wasn’t sure if he would be able to serve and that his role might have been nothing, but it, obviously, turned out to be something. Was he surprised that he could effect this change in this particular area?

BC: In his more insecure moments he would be like “I don’t know why you guys came to Paris, I don’t know what we will even be doing there. I’m not part of a delegation, I don’t know what I’m going to be asked to do with anything, people may or may not ask me for advice.” So, it was unclear what was going to happen.

JS: This is coming from a man that used be at the highest levels of government for years. He was in a unique place where had all this dispersed experience, so to be able to utilize it to bring the first successful international agreement to fruition was just kind of amazing for him and, obviously, given the fact that we had cameras there for that was exciting.

BC: Yeah, he didn’t even ride by motorcade to the Paris meetings. He went to ride the subway [laughs]. That scene is in the film because it was unbelievable and surreal.